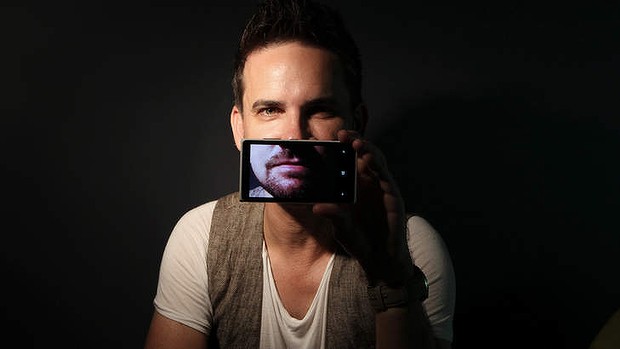

There’s only one problem with Jason van Genderen’s mobile phone – sometimes people call him on it.

For a specialist in shooting films with a smartphone, unexpected calls or texts are a sudden interruption to working. ”The camera stops recording and there’s usually a few expletives,” the NSW central coast filmmaker says.

But that is clearly only a minor obstacle given van Genderen, 41, has won eight international competitions – the latest being at Sundance London – with short films shot on phones.

One of Mr Van Genderen’s stills Photo: Jason Van Genderen

One, a touching short about homelessness called Mankind is no Island that won Tropfest New York, has been viewed more than a million times on YouTube.

”It’s totally unintentional,” van Genderen says of a niche that is putting the ”art” into ”smartphone”.

While he also makes films with other cameras and creates online content, he discovered his talent with a mobile when he won a Sydney Film Festival competition five years ago. That short, My Town Is Broken, used street signage to show the decline of Gosford’s commercial centre.

One of Mr Van Genderen’s stills. Photo: Jason Van Genderen

But is it a legitimate form of filmmaking or just a gimmick?

”In its very early form, it was very gimmicky,” van Genderen says. ”But you choose a tool that’s appropriate for the story you want to tell. ”You’re not going to be able to film some blockbuster epic on a portable camera device. But for very simple stories that only really need the equivalent of a digital Box Brownie, there’s no reason you can’t use smaller equipment.”

Using a discreet smartphone camera helped when it came to shooting a film about the impact of hip-hop on an Aboriginal community. It won a $5000 prize at Sundance London last month.

”If I’d walked in there with a big camera and a camera crew, it would have been a far more difficult process to get the response that I did,” van Genderen says. ”You point a smartphone at someone and ask them to say something, they find it a lot easier to talk than sticking a large-format camera in their face.”

He holds the phone for moving shots, uses a tripod for stationary ones and edits on a laptop.

”Every six months we’re seeing great shifts in what we can do with lensing,” van Genderen says. ”But the software in most smartphones is still really basic unless you download apps [to manually control focusing and other camera operations].”

Five years ago, American filmmaker Spike Lee linked up with Nokia for a movie made with mobile-phone footage from everyday people. Two years ago, two little-known filmmakers shot another movie, the US family drama Olive, with a smartphone taped to a set of traditional film camera lenses.

Van Genderen believes a mainstream movie will be shot on a mobile one day. ”You could create an Academy Award-winning short film on security cameras if the story is riveting enough and if the technique lends itself to it being told that way,” he said.

”It’s the same with smartphones or mobile cameras of any form. If you can come up with a story that uses the medium really well, so that when an audience sees it they forget what it’s been filmed on, you’ve got a win-win combination.”

by Garry Maddox