Cinematic pioneer who created monsters and inspired many of our greatest film-makers

Wendy Ide

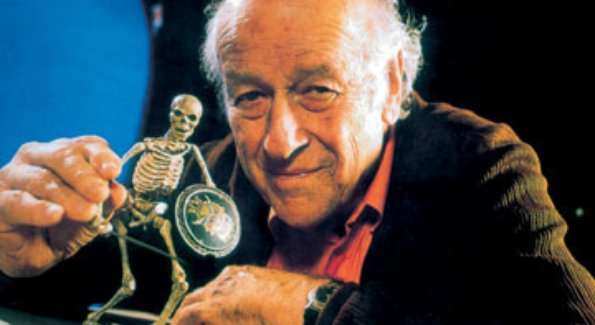

In the sitting room of the West London home of Ray Harryhausen, the special-effects pioneer and stop-motion animation legend, there is a shelf that bristles with awards, including the lifetime-achievement Oscar that he was presented in 1991. There are exquisitely crafted bronze figures of some of the most iconic creatures (he prefers the more empathetic term “creature” to “monster”) from 20th-century cinema. And on the coffee table are two mugs of tea, a plate of ginger biscuits and Medusa, one of the stars of the original 1981 version of Clash of the Titans, which was recently remade as a 3-D, CGI extravaganza. “I haven’t seen it. It’s somebody else’s interpretation. They wanted me to get involved [in the remake] but I just couldn’t.” This didn’t stop the film-makers borrowing heavily from Harryhausen’s distinctive vision.

Medusa is 20in tall and has fixed me with a disdainful glare from her icy blue eyes. Her headful of writhing snakes are poised to attack. From this intimate distance, it’s clear that her scaled torso has been rendered in painstaking detail, and even the musculature beneath her reptilian skin is visible with unnerving clarity.

For someone who devoured Harryhausen’s miraculous fantasies as a child, who grew up on Jason and the Argonauts, The 7th Voyage of Sinbad and One Million Years BC, meeting this diminutive but formidable model is almost as exciting as meeting her creator. Harryhausen, distinguished, snowy-haired and forthright, regards Medusa with obvious affection.

There was a continuing debate with the studio, he recalls, about whether or not she should wear a bra. In his original drawings he equipped her with a kind of boob tube to preserve her modesty, but for the final film he threw caution to the winds and revealed her in all her scaly glory. He points out a tiny detail — she has little tufts of underarm hair.

Medusa is, in fact, a very complex piece of engineering, and, together with the famous seven-skeleton battle sequence from Jason and the Argonauts, represents one of the greatest technical achievements of a man regularly described as a genius and one of the most influential special- effects wizards in cinema.

Harryhausen quibbles about his status, preferring to pass the credit to Willis O’Brien, the visual-effects supervisor on King Kong (1933) and the man who gave Harryhausen his first feature film job, on Mighty Joe Young (1949).

But it is Harryhausen who, on the occasion of his 90th birthday this month, will be celebrated with an exhibition of his drawings, models and film footage at the London Film Museum, and by a collectible limited-edition book called Ray Harryhausen: A Life in Pictures. And it’s Harryhausen who is cited as an influence by film-makers from Steven Spielberg (“I salute him every day”) to James Cameron (“We all owe Ray a great debt”); from Pixar (who named a restaurant after him in Monsters Inc) to Tim Burton (who said Mars Attacks! was a direct homage).

Nick Park, the Oscar-winning animator behind Wallace and Gromit and another avowed Harryhausen fan, says that Gromit’s famously expressive eyebrows were partially inspired by those of Mighty Joe Young. “I remember seeing Ray Harryhausen on I think it was a TV programme called Screen Test. I just got to work straight away in my own little attic studio. I made a brontosaurus out of coat-hanger wire and foam and my mum’s old tights.”

Park treasures the memory of his first meeting with his hero 20 years ago, when Harryhausen strode up to Park, then unknown, after a screening of Creature Comforts and complimented him on the “best bit of clay animation I have ever seen”. “I think his work made me hungry to be a film-maker,” Park says. “It gave me an ambition and that desire.”

But for all the film-makers who cite Harryhausen as a crucial influence, there is nobody today who works in the way that he did. For almost all his feature films, Harryhausen worked entirely alone, from the initial design of his creatures and the hundreds of sketches to the meticulous, fractional frame-by-frame movements that add up to the flowing battles and lumbering monsters that delighted generations of movie fans. Harryhausen chuckles. “I preferred to work alone because I don’t like to have people talk me out of ideas.” It wasn’t until his final feature film, Clash of the Titans, that Harryhausen finally conceded and took on a pair of assistants — and then only because a sprocket-stretching problem with the film stock had left the film well behind schedule.

He’s incredulous about the vast crews employed on contemporary action and fantasy films. “You read the credits for films today and there are a thousand people working on one thing. It’s vulgar the expense — $200 million [£136 million] to make a film! We made the 7th Voyage for $650,000.”

There’s a Scout’s make-do-and- mend ingenuity to Harryhausen’s work. He confides, as we admire the magnificent Medusa, that he would have preferred to give her red eyes, but because he had to use existing doll’s eyes, that wasn’t possible. It wouldn’t have occurred to him to waste money on having them specially made. Earlier in his career, when creating the rampaging giant octopus for It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955), budgetary constraints meant that he was forced to sacrifice two of the eight tentacles. Even with just six, the beast still managed to destroy the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, so perhaps it was for the good of the Bay area that it was handicapped in this way.

So where did his passion for misunderstood monsters come from? Harryhausen was born in 1920 in Los Angeles, an only child who was initially far more intrigued by the traces of prehistoric life to be found at the local La Brea tar pits than he was by the thriving motion- picture industry. Two films had a colossal impact on him: the first was The Lost World (1925); the second and more important was King Kong (1933). The 12-year-old Harryhausen had tickets to see the film at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, where the film was preceded by an elaborate show of trapeze artists and acrobats. “It was an event in those days to see a film. You would wait for Saturday night to see the new picture. But today you are inundated with entertainment. I think the magic has gone out of it a little, yes.”

Harryhausen estimates that he saw King Kong some 200 times and credits the film as the reason he ended up working in the film industry. It triggered a lifelong fascination with how the onscreen dream was created.

He set about experimenting with his own animated action sequences. The first creature he made was a cave bear. “Why a cave bear? Well, I cut up one of my mother’s fur coats.”

Mr and Mrs Harryhausen were supportive of their son’s passion. As the experiments progressed, his father donated the family garage as a studio and his mother sewed costumes. Until his death, Harryhausen’s father made the metal armatures about which the models could be constructed.

Ray Harryhausen’s career took him from Frank Capra’s Army film unit in the Second World War to battles with a Cyclops or an army of skeletons; it let him create a series of animated fairytales for schoolchildren and to pulverise the cities of New York, Rome and San Francisco. It let him, crucially, retain a sense of childlike wonder and a love of fantasy and escapism. “I always say films were invented for fantasy, otherwise they just become propaganda. Now the films are so serious — everybody has a gun and they are shooting everybody.”

So what does he make of the massive technological advances in cinema special effects? “Well I think CGI is a wonderful tool, but only a tool. I don’t think it’s the be all and end all. The whole point of making a film is to entertain, or so I thought. Not to give you somebody else’s propaganda.”

He will concede, however, as a lifelong fan of dinosaurs, that he admired Spielberg’s Jurassic Park. The state-of-the- art motion-capture technology used on films such as The Lord of the Rings trilogy, meanwhile, is not quite as novel as people assume. “They did that with Snow White,” Harryhausen says. “They rotoscoped Snow White and then the animators worked on the footage. You don’t follow it directly but you photograph the person going through the actions. That’s the way they made Snow White so realistic. So there’s nothing new under the sun.