He’ll hit her – and think it feels like a kiss

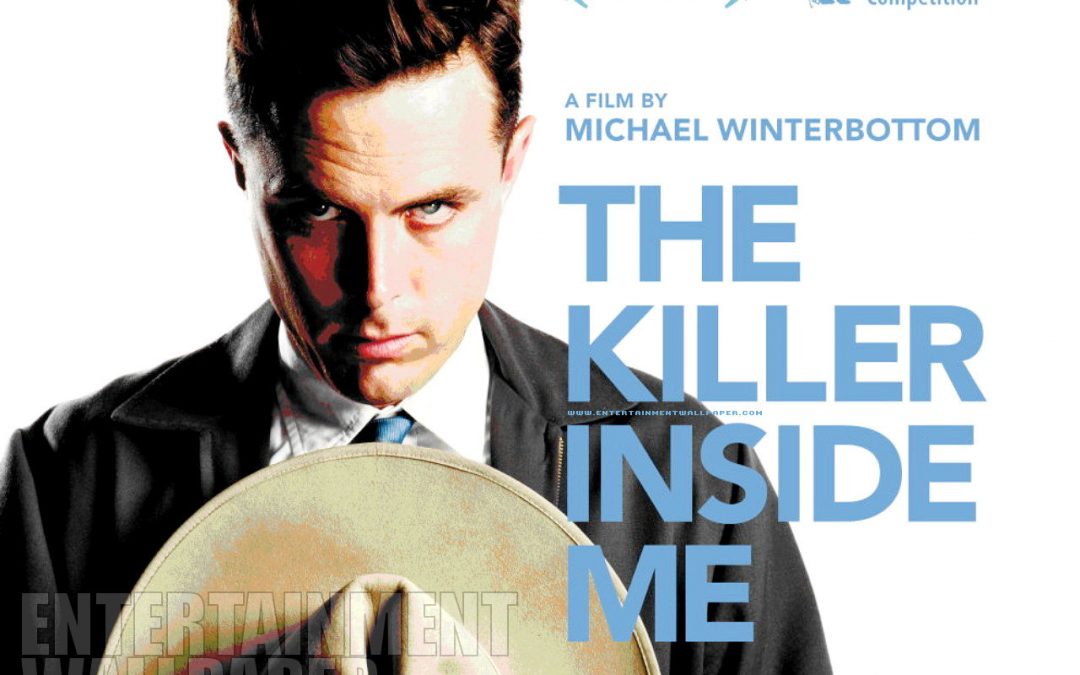

The most disturbing film of the year is The Killer Inside Me. For its director, Michael Winterbottom, the violence had to shock.

Stanley Kubrick described it as “probably the most chilling and believable first-person story of a criminally warped mind I have ever encountered”. That’s some commendation, not least from Kubrick, who had a propensity for challenging material, and whose films — Lolita, A Clockwork Orange, The Shining — featured some deliciously warped individuals. The novel was Jim Thompson’s 1952 pulp-fiction classic The Killer Inside Me. Kubrick had employed Thompson as a writer on his crime drama The Killing and his anti-war film Paths of Glory, in the 1950s, but, perhaps surprisingly, didn’t go on to make a screen version of The Killer Inside Me himself. Not even he, though, would have brought Thompson’s novel to the screen with more visceral, gut-wrenching punch — punch being the operative word — than Michael Winterbottom.

The new version by the prolific, versatile British director stars Casey Affleck as Lou Ford, deputy sheriff of a small Texas town and a cold-blooded killer, one of those compelling antiheroes with one foot expertly placed in each camp. Narrating his own story, this seemingly mild-mannered cop — who lives by the motto “Out here you’re a man and a gentleman, or you’re nothing at all” — kicks off proceedings with a double murder, ostensibly to settle an old score, and keeps killing to cover his tracks.

As in the book, the scenes of violence are unequivocally shocking, their impact compounded by the fact that Ford’s key victims are women — played by the game A-listers Jessica Alba and Kate Hudson — whom he beats to a pulp with matter-of-fact thoroughness. In each of the two screenings of the film I have attended, it felt as though the cinema seats were buckling under the audience’s collective unease. At the film’s premiere, at this year’s Sundance festival, the first question to the director, from a woman in the audience, was, effectively: “How dare you?”

“I was watching the print for the first time myself, because we had rushed to get it to the festival,” recalls Winterbottom, who was visibly taken aback by this attack. “The sound level was too loud in there — it was weirdly loud — which didn’t help. The killing scenes were even louder than they should be, and even more grotesque.” He laughs. “But that woman didn’t walk out. And I was slightly more ready at the next screening.

“The film is shocking, I think, specifically because it’s to do with violence against women. Also, because Ford has a close relationship with both these women, there’s an added perversity to his actions. To me, it would be far worse to do a film about a killer who is crazy that isn’t shocking. The violence shouldn’t be enjoyable. That’s the point.”

This is not new territory for Winterbottom: a few years ago, his 9 Songs whipped up minor controversy with its explicit sex scenes, making him the first British director to align himself with the increasing realism among European art-house directors in presenting sex. He may be as speedy and seemingly carefree in his film-making as Kubrick was painfully meticulous (Killer is his 18th feature film since he graduated from television series such as Cracker in 1995, with Butterfly Kiss), but he shares with him an unerring focus on the integrity of his material. He first came across Thompson’s novel a few years ago and immediately wanted to know who owned the rights. He located two American producers who had been trying to make the film for 14 years, with a number of directors. They had finally found their man.

Thompson is regarded by some as the premier pulp-fiction writer — tougher and more disturbing than Chandler or Hammett — and his books have spawned several film adaptations, including The Grifters, After Dark, My Sweet, two versions of The Getaway and a 1976 version of The Killer Inside Me, with Stacy Keach as Ford. Winterbottom’s customarily breathless, rat-a-tat delivery seems more pronounced than usual as he recounts his enthusiasm for the novel. “When I first read it, it stayed with me for a long time afterwards. It’s very rich. It has all those qualities of hard-boiled fiction, but is also quite tender and complex. There was a sadness about it. The fascinating thing is that you see this character who does perverse things, who destroys people who love him, and whom he seems to love and could be happy with. He has a connection with them, even as he’s killing them. There’s a feeling of waste, a possibility of love that is being lost.

“Everybody does things that are self-destructive to a greater or lesser degree. Lou is an extreme version of what you see around you in real life. It may sound pretentious, but it’s almost Shakespearian in the way Thompson has created a character you feel embodies a lot of the flaws everyone has.”

The director is sometimes chided for not giving the audience the explication and emotional payoffs that, for good or ill, they are accustomed to. He has said to me in the past that he doesn’t like cinema “where you feel you’re being forced or manipulated into a particular emotional response”. With The Killer Inside Me, his coolness perfectly complements Thompson’s. Even here, though, he pares down exposition to make already difficult material even harder to bear. In a script (by John Curran) otherwise notable for its fidelity to the novel, the one thing that’s missing is Ford’s first-person allusions to his madness — a self-knowledge that slightly mitigated his psychotic behaviour.

In the 1950s, Thompson’s talk of schizophrenia and child abuse would have been radical (as was Hitchcock’s in his 1960 film Psycho), but today — when Dexter’s tiresome musings, say, offer only diminishing returns — one really doesn’t need all that. “In the book, there are various explicit explanations as to why Lou does what he does, but I wasn’t interested in his psychological condition,” Winterbottom asserts. “Thompson is portraying this world where people destroy their lives, destroy other people’s lives, for whatever reason. He captures something true. You don’t need to explain it.” When I suggest that this is asking a lot of the audience, he answers: “Oh, yeah.”

He is aided and abetted by a terrifically deadpan, ambivalent performance from Affleck, maintaining the standards he set in The Assassination of Jesse James and Gone Baby Gone. “I wanted the audience to get a sense that Lou Ford’s interior world is at odds with how he behaves. Casey’s a brilliant actor like that, doing one thing, but suggesting he might be thinking about something else entirely.” As for the violent scenes, Winterbottom says it was the actor, not the actresses, who found them difficult. “It seemed to me, on set, that every time we had any violence, it was Casey who was stressed about doing it. But everyone knew what they were doing in advance, so it was not a sudden surprise.” Affleck, for his part, says he and Winterbottom talked about the violence at length before the shoot, and the actor was okay with the idea that it would be depicted in a brutally realistic way. “I thought, ‘Well, this is not going to glamorise violence or desensitise the viewer, it’s going to be upsetting.’ That’s what it ought to be.”

Winterbottom has found an added layer of twisted irony in his period soundtrack: when you hear Spade Cooley sing Shame on You, it’s worth remembering that “the king of western swing” beat his wife to death. Like Lou Ford, he never stopped professing his love.